If you’re a student of Japanese culture, it can be a little hard to see how Okinawa is different from the rest of Japan. Although they were an independent kingdom for centuries, they were conquered by Japan 400 years ago—that’s a long time for a conquered people to maintain their culture identity with integrity. But the Ryukyuan people are persistent, and the Japanese benefitted from the façade of “business as usual” in the kingdom for centuries, so not as much has been lost as for other indigenous people. Although there are many places around the island that showcase traditional Ryukyuan culture, one of the most popular is Okinawa World.

Our first stop was Gyokusendo Cave (which I’ve covered in a more philosophical vein already). The air was cool and thick with humidity, and being huge geology nerds, my mom and I dashed between formations in awe: “Look at the little straws!” “Oh, what pretty drapes” “Holy crap, this stalagmite is huge!” In addition to the formations, there were also many displays: archeological remains (mostly pottery shards and ancient coins), signs about the animals that live in the cave (almost all fish and snails), sake jars brewing drink, and a stone pot left in the cave in 2012 to show the progression of mineral formations over time, the fresh stone a fragile layer over the clay. There were also light displays to highlight the texture of the ceiling or a particularly deep pool or an especially beautiful formation. We took a hundred photos that blurred and changed color and came out grossly underrepresenting the magnificence of the cave, but then it was time to go back into the light and find other things.

We passed an orchard in bloom—like everything else on the island—and decided against the Glass Studio where tourists can make their own Ryukyuan glass, knowing we wouldn’t have time later to pick up our fully-cooled creations. We dove into the traditional crafts village instead, where Loren and I suckered mom and dad into getting dressed in traditional robes while holding back ourselves. The traditional village was like a Ryukyuan-themed Disneyland, and the traditional crafts were the rides. Everywhere you looked you could buy an authentic experience with the traditional culture, which sounds about a real as buying authentic friendship. We passed leatherworking, weaving, papermaking, three kinds of cloth dyeing…Then suddenly mom found the one activity she couldn’t live without: sanshin playing!

The sanshin is cousin to the shamisen, both distant cousins to the banjo. Mom loves all stringed instruments on principle, but her actual experience lies with guitars and banjos, so she was very excited to try the sanshin. We approached the teacher and asked for a lesson.

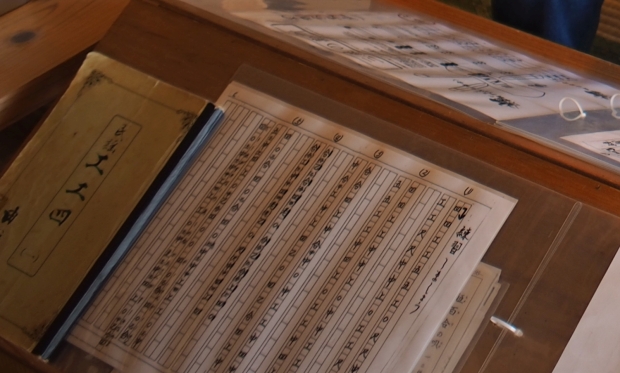

He seemed surprised that mom was interested—I figure he doesn’t get a lot of foreigners of any kind—but welcomed us in as his only customers. We sat on a long bench and he showed mom how to hold the sanshin and the plectrum, then provided written music of a very different tablature than either mom or I had ever seen. Rather than notes on five lines, or even Arabic numbers on three lines (like shamisen tablature) it was Japanese writing paper with lines running top to bottom, and inside were written a combination of Chinese numbers, prepositions, and other characters that didn’t seem to make sense in music.

The teacher explained, and it turns out that the tablature is quite simple, and the simplicity makes it hard to remember. Just like in Western tablature, each note gets a unique notation on the page (e.g., the three Gs on a treble scale stay on their own line; no other note goes on one of those lines), but unlike Western tablature, names aren’t reused each octave; instead, each note playable on a sanshin gets its very own name and notation. On the one hand it’s good—there’s literally only one way to play a given note—but it’s also hard because in order to play anything, you have to map a specific symbol to a specific hand position in your mind. It was a little easier for me to read the music (since I could both understand the instructions and was at least marginally familiar with all the characters used in the tablature) but for mom it was like reading tea leaves. I did my best to help by showing her the correct hand positions and trying to come up with memory tricks for the characters that went with each note, but it was a long process.

We struggled through the first piece note by note, and the teacher played with us. He encouraged mom and I translated the encouragement, adding my own as well. After playing through the first round of notes too slowly to understand the song, the teacher had us play it again. Mom was a little more pulled together this time and we finally eked out the melody: “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star.” Unfortunately she was still making copious mistakes, and each time she caught one she pulled her hand from the sanshin like she’d been burned.

After a third round she seemed to be in an odd place: on the one hand, she wanted to give up, but on the other hand she wanted to keep going. The teacher, though, was clear: he wanted her to play one song before she left, and it was going to happen! He continued to coach her, relenting on issues of form to focus on helping her find the right notes. We played over and over, and at the end, mom stumbled out a slow but basically correct rendition of “Twinkle Twinkle!” We were all exhausted and relieved, and we sat with the teacher a few moments more to talk with him. Apparently he’d been playing for thirty years! We were very impressed and asked him to play something for us, so he played a traditional piece much more complex than “Twinkle Twinkle.” It was lovely, very similar to the shamisen pieces I’m familiar with in Japan but also different in a way I couldn’t put my finger on.

As we walked out of the Traditional Crafts Village, we found that the eisa dances were just starting. Eisa is a traditional form of dance in which several dancers, drummers, and sometimes a sanshin player work together to do acrobatic dances and techniques. While some dances displayed the dancers’ skill, others told stories: one in particular was about an old man and old woman who owned a shiisa lion-dog. They had the shiisa do tricks and play fetch, the movement so realistic it was jarring to think of it as just two incredibly coordinated people in a costume. At the end, guests were invited forward to have their heads “bitten” by the shiisa mask, which is considered good luck. Although the music reminded me quite a lot of the Japanese folk dance music, the dancing had stronger Chinese influences.

The last part of our visit took us to the Habu Center, which teaches awareness, safety, and familiarity with the island’s most dangerous snake, and snakes in general. A museum in the center highlights the ways the islands have decreased habu bites, how antivenom was discovered and how it works, the skeleton of a typical habu (as well as the twenty-foot skeleton of a massive python), how habu fangs work, and other seriously cool hands-on exhibits.

The highlight of the Center is the habu show, in which trained staff show the living animal, demonstrating its coloring, striking range, striking speed, how it senses prey, and its other characteristics. They even had a swimming race between a habu and an irabu sea snake (the black-banded sea krait), which are also endemic to the island chain. (Fun fact: irabu are simultaneously one of the most venomous snakes in the world and also one of the least dangerous to humans, as they’re nocturnal, shy, and curious rather than aggressive. ♫The more you know…♫) Both snakes were placed in a chamber above a long, clear acrylic box with about six inches of water in the bottom. On “go” both snakes were released into the water with a trapdoor. I’d expected the irabu to smoke the habu, but the habu made a clear victory—although habu can swim well, they don’t like it, but irabu live in the water and are naturally curious. While the habu made a beeline for the end of the course, the irabu hung out near the start and explored.

At the end of the show, the staff brought out a python for guests to interact with. I love snakes, so I shot my hand into the air when they announced that some guests would be allowed to hold it and get a picture with it. My brother and I were both selected and we went forward to a set of chairs where we sat as the staff draped the boa over us like a living shawl. Its scales were very smooth, and I could feel its strength as it adjusted itself over my shoulders to get more comfortable.

When we left that day, I’m not sure that I had a better feeling for Okinawan culture as distinct from Japanese culture, but I’d had fun and learned a bit about what Okinawans consider important about themselves.

Address: 1336 Tamagusuku Maekawa, Nanjo-city, Okinawa Prefecture, 901-0616

Price: Varies depending on the attractions you want:

- All attractions: 1600 yen (~$13 USD), 800 yen children 4-15

- Cave and village only: 1200 yen (~$10 USD), 600 yen children 4-15

- Village only: 600 yen (~$5 USD), 300 yen children 4-15

- Habu Center only: 600 yen , 300 yen children 4-15

Tips:

- Don’t miss the cave! If nothing else, it’s a good place to get out of the sun or rain, and it’s honestly very cool.

- Bring plenty of extra money for the village. There are tons of crafts to try in the village, but they aren’t free. That said, the costs are extremely reasonable—our sanshin lesson was 30 or 45 minutes for 500 yen (~$4 USD) if I remember properly.

- You may see several negative reviews online about the treatment of snakes at the Habu Center. As of my visit in 2014, the issues with bare enclosures and rough treatment of the snakes appear to be resolved. They also no longer showcase fights between mongooses and snakes, to the despair of terrible people everywhere.

- With the exception of the cave, all parts of Okinawa World are “barrier free” and wheelchair accessible.

Great info. Thank you for sharing. I like the part about the sanshin.

LikeLike

Thank you! The sanshin lessons were more fun than I expected; the teacher was extremely patient. 🙂

LikeLike